The Neuromarketing of Emotional Memories and Commercials

Photo Stephen Monterroso, Unsplash

Consumers are a lot like Lucy (Drew Barrymore) in the rom-com 50 First Dates. Lucy, unable to remember each waking day due to memory loss, meets Henry (Adam Sandler)—a womanizing veterinarian. Despite his fear of commitment, he strives to win her over again each new day. We may not have short-term memory loss and a Henry to charm us every day, but we do have commercial ads that try.

We’ve all had a vague memory for a commercial. Maybe we remember the storyline, who was in it, or what it was about, but we can’t remember what it was a commercial for to save our life. This is a true failure from a brand’s perspective.

When brands create commercial ads, they are in the business of feelings—creating a strong impression. Imagine having watched the most entertaining commercial. If someone were to wave the Men In Black wand in front of you and zap it from your memory, it would cease to have any value for the brand at all.

This is why experiences mean nothing for consumer behavior if they don’t create strong memories. To boost a commercial’s stickiness, brands often turn to emotion.

As we’ll see, emotion can often serve as a double-edged sword. It’s a potent force, and when it isn’t harnessed correctly, it can produce surprising results. To understand this, let’s see the impact of neuromarketing in emotional memories.

The Neuromarketing of Emotional Memories

We all remember our “firsts”—though some more vividly than others. This is because emotion is strongly tied to memory: the more emotional an experience, the more likely we’ll remember it later. By sticking attention and memory together, emotion acts like super glue.

Emotional experiences are simply prioritized by the brain. Whether good or bad, if something is important enough to arouse our emotions, our brain assumes it’s important and therefore should be remembered. That’s why we often never forget our first kiss and first heartbreak.

This prioritization of emotional memories likely bears evolutionary importance. Highly emotional memories, such as being chased by an animal or eating spoilt berries, are lessons worth remembering to increase survival. Emotions tell the brain what events to tag with a label reading “important!”, boosting encoding (the brain’s way of processing information) and strengthening the impression.

This memory prioritization effect takes over more with emotionally-charged experiences—like being in a car crash—than mundane ones, but also with simple stimuli like text.

Emotionally-charged words like love, hate, and happiness are encoded and recalled with greater accuracy than neutral words like desk, money, and highway. So it’s no surprise that emotional words are used extensively to drive attention (and ultimately memory) in different marketing contexts—billboards, banner ads, and search results.

From a brand’s standpoint, what matters isn’t the emotional experience, but the memory it will be associated with later on. But emotions aren’t just buttons to press to fuel an impression and supercharge a memory. It turns out they’re much more complicated than that.

Why Turning an Emotion to a Memory is Complex

For a brand to be effective, they also have to connect the right emotions and attributes in the consumer’s brain, and in such a way that ensures these elements are associated with the brand itself.

Tying an emotion to its true cause is surprisingly difficult. Say you feel a bit down for no apparent reason—is it because of some deadline you’re unconsciously dreading, or is it because it’s dark and raining outside?

This difficulty in tying down the source of an emotion is common. It’s especially potent for the most fundamental of emotions: emotional arousal or the fight-or-flight response.

Arousal is the feeling of our body getting primed for action. Our sympathetic nervous system comes online—our blood pumps quicker, and breathing becomes shallower. This physical response is core to our survival. Without one, our ancestors would’ve never found food in the open because they turned into food instead.

Fight-or-flight response is, however, a bit of a misnomer. The same system comes online for sexual arousal as well, leading some risqué researchers to describe it as the three Fs response: fight, flight, or . . . insert everyone’s favorite F-word here.

Since we’re notoriously poor at correctly identifying why we feel a certain way, this can lead to some confusion. Do I feel stressed because of the test I’m headed to, or because of the aggressive homeless guy I just saw on the subway? Both of these situations can produce the same feeling, making it hard to know exactly what prompted it. Cornell University in upstate New York provides the perfect setting to study this phenomenon—what scientists call misattribution of arousal.

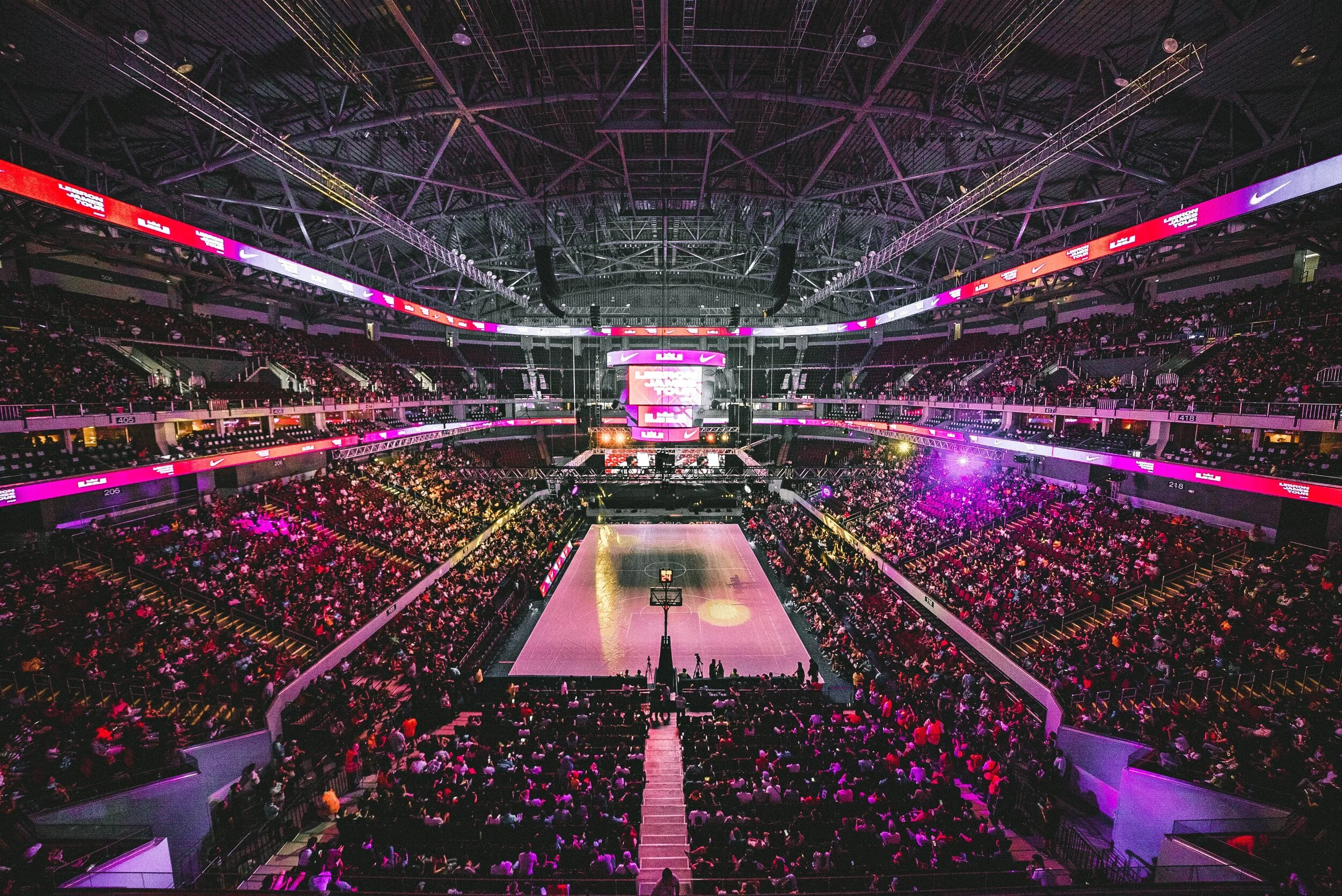

Cornell is set in idyllic Ithaca, which is surrounded by gorges; several parts of campus are connected by bridges overlooking them. The bridges, though perfectly safe, are scary to walk across. In a now classic study, Cornell psychologists enlisted the support of a female student. As male students walked by, she had them fill out a brief survey.

After they completed the survey, she—in a move unusual for a scientific study, but acceptable during the pre-dating apps era—gave them her phone number. As you may imagine, the survey was irrelevant. What researchers wanted to know was how many called and asked her out. The study had two scenarios, one in which she spoke to the students before they crossed the bridge, and the other after.

The arousal from crossing the bridge had a major effect: those who interacted with the woman after they crossed the bridge were far more likely to call her. Having just crossed the bridge, they were more aroused than usual.

Their palms were sweaty, and their hearts were beating. But they attributed this not to the bridge, but to their interaction. They thought, Wow, I was really into that conversation; maybe there was something there. Let’s give her a call. Subsequent research has replicated the study and extended them to other genders and sexual orientations. The result remained similar.

The takeaway here in everyday life is if you want to be an accurate judge of how attractive the other person is on your first date, don’t do anything that will perturb your autonomic nervous system—no coffee (a stimulant), no roller coasters, and definitely no parkour.

In the consumer world, this means brands need to be careful in how and when they insert their brand into an emotional storyline. Here are the two forces that drive consumer behavior.

The Psychology of Associations and Emotional Timing in Advertising

Given what we know about its role in encoding memories as a booster, the fact that advertising uses emotion isn’t surprising. To create an implicit association, successful emotional advertising involves creating intentional misattribution of emotion to convince consumers to attribute the emotion an ad stirs up to the brand instead.

One way this has manifested is the classic commercial convention of creating a captivating, emotionally engaging ad that only reveals the brand at the very end. If you can recall an example of a commercial that, although emotional, had nothing to do with the brand’s product itself, you’re on the right track.

Take this ad that aired on national TV in the UK. It starts off with a preteen boy opening up a box of items that belonged to his dead father. Eventually, he approaches mom in the kitchen to utter the opening dialogue: “What was Dad like?” The rest of the commercial is mom taking the boy on a walk, on which she answers his question.

Guess what the commercial’s selling. Life insurance? Luxury watch? Financial planning? Not even close. The pair walk into a fast food restaurant to order a burger. The commercial cuts to a McDonald’s logo. The end. The McDonald’s “Dead Dad” commercial is a clear attempt at emotion design.

Unfortunately, it was likely a failed one from the perspective of memory. Even if the commercial succeeded in playing your emotional heartstrings and implanting itself into your memory, what good is it if consumers forget which brand it was advertising?

Studies have found that while this kind of ad is effective at grabbing attention, viewers are less likely to associate the ad with the brand. When a brand is flashed at the end, the brain only starts associating the commercial with the brand at that instant. And considering you’re likely not thinking about this commercial for too much longer afterward, your brain only thinks about the brand for a few seconds during the end of the ad—not nearly enough to create a strong connection.

If the commercial had revealed at the outset that it was for McDonald’s, at least then your brain would’ve formed this association for the duration of the commercial, giving it a much greater chance of remembering the commercial. As it is, if this commercial somehow comes to mind, you’d only be able to think to yourself, “Oh yeah, I do vaguely remember that strange, depressing commercial about a dead dad. That was a car insurance ad, right?”

The power of setting up association in the beginning, if done right, can make all the difference. Take it from Henry in 50 First Dates who got Lucy to fall in love with him every day despite her memory loss. How? By replaying the “Good Morning Lucy” video tape every morning, which recaps everything—from the accident to their wedding.

Imagine how over the moon companies would be if they figure to channel their inner Henry to the Lucy in all of us…

What’s Next?

References

“McDonald’s Dead Dad Advert,” YouTube video, May 15, 2017, 1:30, posted by “anarchi.st,” May 15, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S1XM4INk8l8.

D. G. Dutton and A. P. Aron, “Some Evidence for Heightened Sexual Attraction under Conditions of High Anxiety,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 30, no. 4 (1974): 510–17, doi:10.1037/h0037031.

Ferreira, Paulo et al. Grabbing attention while reading website pages: the influence of verbal emotional cues in advertising. Journal of Eye tracking, Visual Cognition and Emotion, [S.l.], June 2011.

Fox, E.; Russo, R.; Bowles, R.; Dutton, K. (2001). Do threatening stimuli draw or hold visual attention in subclinical anxiety? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 130 (4): 681–700. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.130.4.681.

G. White, S. Fishbein, and J. Rutsein, “Passionate Love and the Misattribution of Arousal,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 41 (1981): 56–62, doi:10.1037/0022-3514.41.1.56.

Kensinger EA, Corkin S. Memory enhancement for emotional words: Are emotional words more vividly remembered than neutral words?" Memory and Cognition 2003; 31:1169-1180.

W. Baker, Heather Honea, and C. Russell, C., “Do Not Wait to Reveal the Brand Name: The Effect of Brand-Name Placement on Television Advertising Effectiveness,” Journal of Advertising 33, no. 3 (2004): 77–85, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4189268.

Dive into the fascinating intersection of psychology and marketing and how to use psychological biases in marketing strategy.