Marketing Tactics Using The Science of Memory Encoding

Marketing Tips Using Memory Encoding | Photo by Lee Blanchflower on Unsplash

Everything you know about memory is wrong. Memory is a funny thing, you think you know what it is but diving into it neuroscientifically, it is dynamic and dense. After reading this article, you'll be able to understand the neuroscience of memory and set the foundation for marketing that leaves an impression.

So, what is memory? Intuitively, memory feels like a single thing. But what you think of as memory is actually a group of distinct neuroscientific phenomena.

When you go to a museum, the region of the brain involved in gaining knowledge from the experience is called semantic memory. It is different from the region involved in the memory of the museum trip itself which is called episodic memory. Moreover, when you study the facts of a city on Wikipedia, you are tapping into explicit memory. Now, compare that experience to slowly gaining a sense of familiarity after moving to a new city, which is an entirely different type of memory called implicit memory. How about learning a physical skill like a golf swing or a basketball jump shot? Learning a physical skill is considered yet another, separate form of memory called procedural memory.

As you can see, memory is incredibly complex. In fact, when writing Blindsight, memory was the only psychological concept covered in more than one chapter. And a good chunk of labor was dedicated to creating a definition of memory that encapsulates all of these different strands accurately but also makes sense to people who are not neuroscientists. Here it is: Memory is your brain’s attempt at connecting you to the past.

Marketing Is The Business of Memory-Making

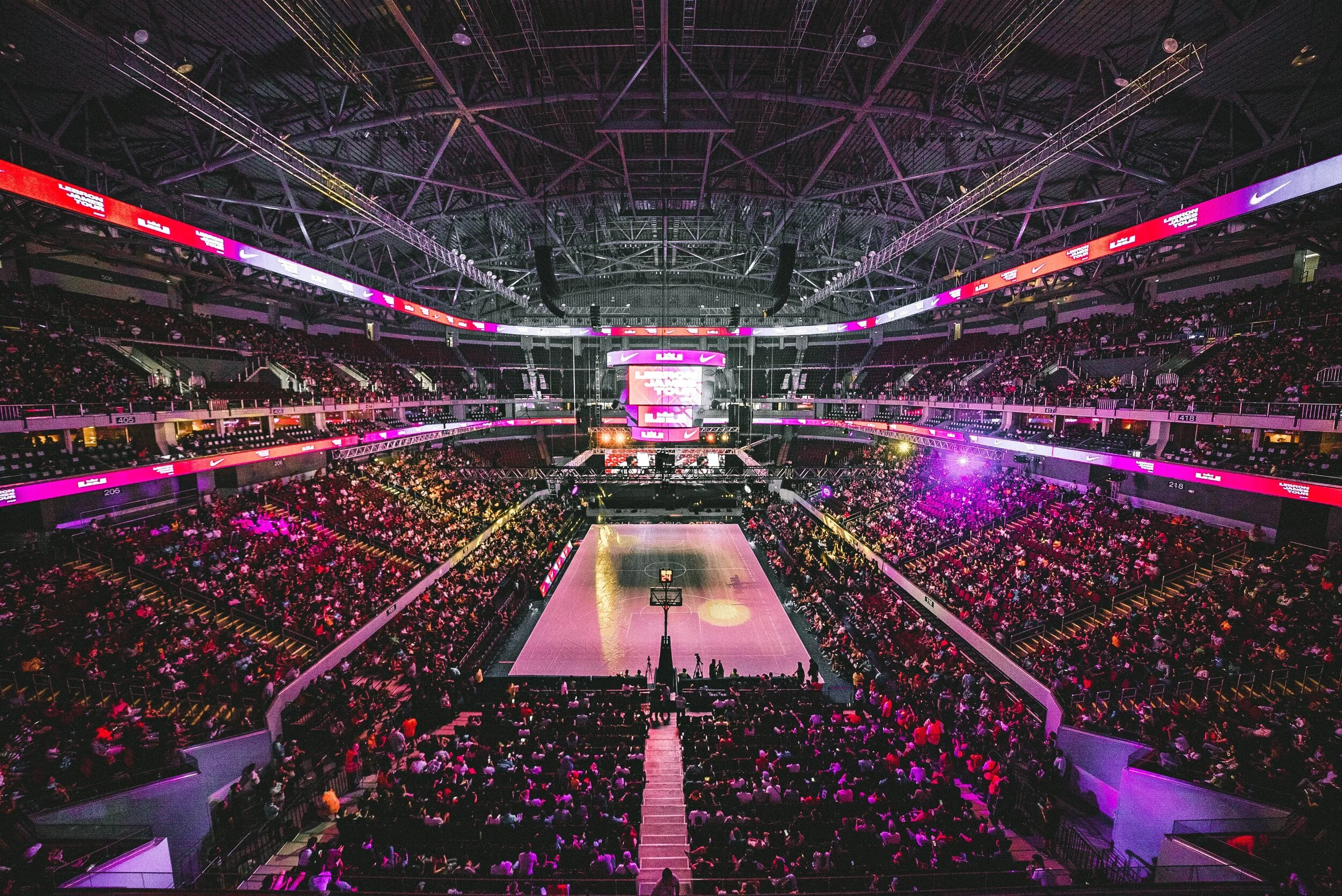

All marketers are in the memory business. The most amazing, gripping thirty-second commercial in the world means absolutely nothing if viewers instantly forget it the second it’s over. An incredibly designed in-store experience means zilch if it isn’t remembered. In fact, when marketers talk about a brand, what they’re really referring to is the cluster of memories of all consumers’ past experiences and previously acquired knowledge related to a particular company, brand, and/or product. For brands, the transformation of experiences into memories, and the effective retrieval of those memories, is crucial. For brands to connect with consumers, they need to become part of the consumers’ memory—a part of their past. As a marketer, contextualize all activations and touchpoints in accordance to memory.

This is the overview of marketing, with much more to build upon shortly. For now, take a moment to sit back and review some of your activations. Think about what impressions would you like to make vs which are actually being made and how can you recalibrate so the marketing will be stored in the consumer’s past?

Here’s a question for you - if you don’t remember an event, did it really happen? Of course, in the larger, objective world, the event took place. But in your world, if no memory of the event exists, neither does the event itself. This is because of something called encoding. The rest of the article covers the brain’s encoding heuristics and see how powerful of an impact enconding can have on a broad range of marketing functions.

Markets Must Understand Memory Encoding

For an event to become a memory, it must first be encoded. Encoding is the process by which the brain turns an event into an impression. Encoding is the verb; an impression is the resulting noun. Impressions are physical things. They are consolidated in the brain’s hippocampus. The hippocampus is located near the very center of the brain, and one of its chief functions is to process memories. Once memories are consolidated in the hippocampus, they are later integrated broadly into the cortex which is the large, outermost region of the brain. For an experience to lead to a memory, it must literally and physically change your brain. It must go from an event to an impression. The consolidation process, or encoding, is what facilitates this first step of memory.

Not every event you experience results in an impression. Say, you had an amazing time wine tasting but drank too much alcohol and don’t remember a thing. So, did the wine tasting really happen? Of course it did. But thanks to the alcohol interrupting the consolidation process, it left no impression on the brain. No impression means no memory. The encoding process was interrupted and the event did not turn into an impression.

For marketers, the success of a campaign should be defined by how strong of an impression it leaves on the brain. Turning events into impressions should be a metric. Turning an event into an impression is akin to encoding it into the consumer’s past. As mentioned, if it does not leave an impression, it doesn’t really matter. Why? because it can’t affect your customers’ future behavior in any way because it never consolidated into their past. Marketers are really in the business of creating impressions—or as a neuroscientist would put it, in the business of encoding.

It’s a tricky business, though, because the transition from event to impression is far from straightforward. Clever brands and marketers should be creating experiences that optimize not only for the event itself, but for the resulting memory. There are certain characteristics of events that can “boost” encoding, resulting in stronger impressions on the brain, such as friction and emotion. Using one or more of these impression boosters can mean a stronger memory that is better optimized to achieve a brand’s goals.

For now, your takeaway is to think of marketing as impression-making. How can your campaigns better encode an experience into the consumer’s past to best contextualize your product, brand, or message for future behavior?

Written by Prince Ghuman

What’s Next?

References

A. Barasch, G. Zauberman, and K. Diehl, “Capturing or Changing the Way We (Never) Were? How Taking Pictures Affects Experiences and Memories of Experiences,” Europe- an Advances in Consumer Research 10 (2013): 294.

Dive into the fascinating intersection of psychology and marketing and how to use psychological biases in marketing strategy.