Pain and Politics: How the Neuroscience of Pain is Applied in Political Marketing

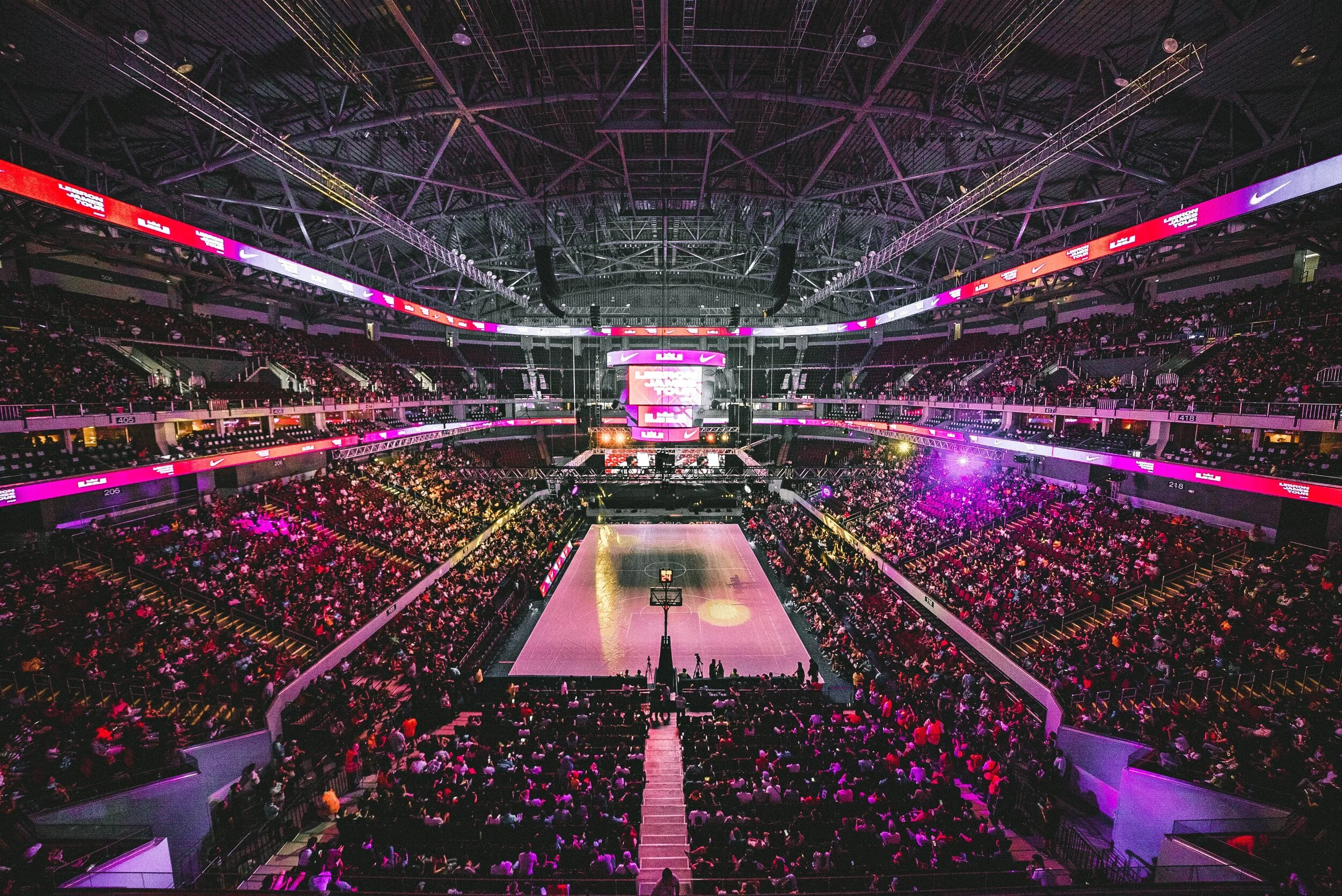

Photo by Karim Manjra on Unsplash

Which stings more - gaining something or losing it?

Losing.

Our brains feel the weight of losses as much heavier than gains. More specifically, the pain of a loss hits harder than the pleasure of a gain.

Loss and gain are analogous to pain and pleasure. Pain hurts more than pleasure feels good. The fear of losing what we already have drives us to make decisions aimed at avoiding this outcome. It makes evolutionary sense: hunter-gatherers felt the pain of missing a meal more strongly than the pleasure of gaining one.

Political campaign managers know pain drives behavior. By tapping into our unique sensitivity to pain and loss, they nudge our behavior towards their strategic direction. To be clear, the above is not limited to the republicans, democrats, tories, or labor party. It applies to all of the above.

Marketing Political Campaigns With Pain Frames

All campaign strategists operationalize the science of loss aversion via what we call the pain frame. A pain frame is a message that is framed to highlight the avoidance of loss, to persuade loss-averse individuals.

The most blatant uses of pain as a persuasion tool involve playing with fear, and clever political campaign managers exploit our fear of losing what we currently have to great effect through pain frames. By emphasizing what we stand to lose by not voting for a candidate, an ad can terrify us into voting for the candidate as the "safe" option. And this kind of marketing is doubly potent in a zero-sum game like the US winner-take-all two-party political system.

Pain frames have been around for decades. Before the 1964 US presidential election, the incumbent Lyndon B. Johnson campaign used fear marketing in a TV advertisement named "Daisy." It opens with a three- or four-year-old child counting up with each petal she plucks from a daisy—one, two, three . . . As she reaches ten, a megaphoned man's voice overtakes hers, this time counting down from ten to one. At zero, the scene cuts to a nuclear explosion. The call to action after the explosion? "Vote for President Johnson on November 3rd."

On the surface, the ad inspires fear, but what it is doing is serving up a dose of pain, the pain of losing loved ones to nuclear war. As soon as the pain is felt, the antidote (in the shape of a product) is presented immediately. In this case, the product is the candidate—hence the immediate call to action, "Vote for President Johnson on November 3rd."

Brexit and Donald Trump Political Marketing Campaigns

A pain frame was especially evident during the 2016 US presidential election and the 2016 Brexit referendum. Take a look at the victors' slogans. In the presidential election, Donald Trump reused Ronald Reagan's slogan from 1980, "Make America Great Again." In the referendum, Team Leave used the slogan "Take Back Control."

Donald Trump Both slogans speak to a loss—specifically, recovering a loss. Trump's campaign claims America has lost its greatness, so let's make it great again. Team Leave says the UK has lost control of its own destiny, so let's take it back. Both slogans use as their frame the pain of losing something. It would be immature to claim the pain frame as the sole reason for victory. It would be equally immature to think pain frames are an accidental feature of political campaigns.

From Political to Product Marketing

To better understand how pain framing works, let's step away from politics and into our day-to-day. Consider the following two questions:

1. Could you live on 80 percent of your current income?

2. Could you give up 20 percent of your current income?

Mathematically, the two questions are the same. Whatever your current income is, both questions pose if you'd be willing to live on the same amount of money. Subjectively, they don't feel the same. Without changing the amount, you can change the feeling of how it lands by merely framing it differently.

Giving up 20 percent frames a pain whereas living on 80 percent frames a gain. The second question initiates feelings of loss in a way that the first question does not. As a result, we are much more likely to say yes to the first question than the second.

Products can be marketed precisely the same way—through either a gain frame or a pain frame. Which of the following messages hits home for you?

1. Our shampoo increase hair growth.

2. Our shampoo prevents hair loss.

Even though the products' effects are the same, the frame makes a massive impact on how you view the product and, perhaps more importantly, whether you ultimately buy it. Especially for those who are particularly loss averse, pain frames tend to be much more compelling.

We tend to be more loss averse when we move from products to politics. Whether by directly instilling fear or framing a message as a loss, optimizing for the brain's pain avoidance is a handy strategy in the campaign manager's tool belt. The question is, will knowing about pain frames stop them from stinging more? You tell me.

Dive into the fascinating intersection of psychology and marketing and how to use psychological biases in marketing strategy.