The Psychology Behind Morality and Virtue on Spring Break

Photo by Prescott Horn on Unsplash

In the Hangover, Alan promises not to speak a word of what happens during Doug’s bachelor party. “Whatever happens, tonight, I won’t ever speak a word of it,” he says.

Like the wolf-pack, we wish our embarrassing memories (whether we remember them or not) could melt away. What bachelor parties are to future husbands, Spring Break is to party-hungry college students. To unearth the humble beginnings of the annual week-long bender, let’s rewind back to 1938.

Back when posting photos of last night’s shenanigans on social media were unheard of, a pack of college swimmers traveled to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. As more teams followed, things went from Ft. Lauderdale to Ft. Liquordale really quickly.

To break athletes free from their mechanical life cycle of sleep, swim, study, repeat, the locals offered beach parties and beers at insanely low prices. What started as a training trip birthed the most anticipated college party of all time.

Today, Spring Break is about forgetting the rules, being reckless, and doing what would otherwise be unthinkable in everyday life. It’s more than just a break in the school calendar; it’s a break from one’s ordinary self.

The desire to experience its craziness represents something deep about the quirks of being human. To understand how we can press pause on our lives to act regret-free, let’s uncover the psychology of virtues and find out how brands lead us to think Spring Break is the perfect getaway to our unruly desires.

The Psychology of Virtues

Our brain is lazy but powerful. To save more energy for serious, deliberate thinking, our brain develops habits or automatic behavior, which require little cognitive effort. Psychologists call this laziness or default system the law of least mental effort.

In relation to Spring Break, it turns out our moral compass—the basis with which we make decisions—operates by the law of least mental effort. In short, default/lazy thinking drives us to do the unthinkable in lit times like Spring Break.

There are few moral rules applicable to every single situation, as Professor of Philosophy Patricia Churchland points out. For example, we turn to white lies when our significant other asks us whether we love their new recipe because we don’t want them to feel bad. We know lying is (universally) bad, but according to our moral rules, a white lie doesn’t hurt if it’s at the expense of hurting someone’s feelings unnecessarily. But memorizing specific moral rules for specific situations is mentally taxing so we develop habits—like the occasional white lie—about what’s right and wrong.

As Churchland explains, “Developing socially considerate habits makes life easier and better for everyone. Habits do not dispense with judgment, but they do reduce the energetic costs of decision-making."

Growing up, our role models taught us how we should behave in society. Over time, the lessons we learned evolved into a set of social norms or habits that drive our behavior, interactions, and relationships.

Social norms are molds based on a set of rules that philosophy greats like Aristotle and Confucius call virtues. Honesty, compassion, courage, and patience are part of the societal constitution we never agreed to obey by, but still do because we want to belong and agree they are good virtues to live by nevertheless.

As soon as our actions conflict with our virtues, we feel we’re prone to judgment and disdain. For instance, Alan didn’t tell the wolf-pack he drugged them (which turned out to be what caused the memory loss), because he wanted everyone to have a great time. Our natural fear of being branded a certain way or even canceled acts as a deterrent, keeping our moral compass intact. (Though beloved Alan is an exception…)

Yet, underneath our virtues lie our most unruly desires—those that make us constantly break the rules, and those we can’t satisfy. These desires are the ignition to our unwillingness to play by the rules.

When our brain gets tired of playing by the rules, it wreaks havoc in many ways—some moderately healthy like binging on ice cream on a cheat day, some not like dancing for 48 hours in a techno bunker. Spring Break, by default, is the way for college kids to do so.

The Brain in Spring Break Mode

A brand new context is kryptonite to an existing habit. Studies have found, for example, that people who love eating popcorn in a movie theater will continue to do so even if the popcorn is stale (insert ‘y tho’ meme here). But if you try to get them to eat popcorn outside of the movie theater (a familiar context), they’ll hardly eat a single piece. Familiar context drives habits, and new contexts break them.

The same is true for virtues and moral habits, and this is amplified on Spring Break. When we switch off normal mode and put on the Spring Breaker suit, we free ourselves from context and break out of a mold. Suddenly, the contextual environment that keeps our typical habits churning is gone. We’re away from the cues of working hard and now free to play harder.

Breaking free of the pull of context and habit, our unruly desires—usually held in check by our virtues—come out to play. Spring Breakers drink ten alcoholic drinks a day compared to six beers on a regular week, more than half have random or unplanned sex (half of which don’t use protection), and 60% have run-ins with the po-po, while many injuries are self-inflicted from recklessness. This is the brain in full Spring Break mode.

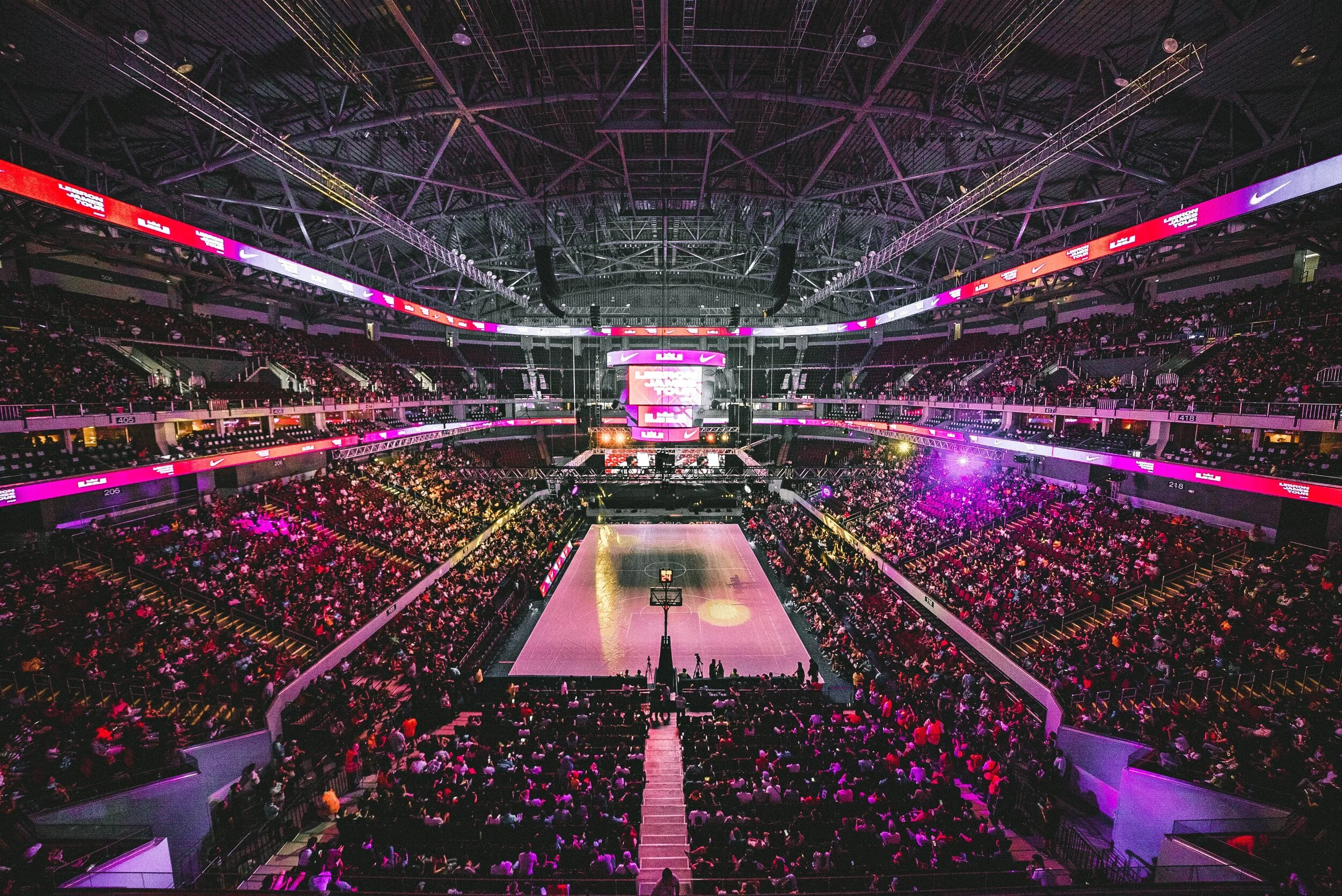

Spring Break is not the only paradise for college kids who want to surrender to their impulses—but it’s also a heaven for brands, travel agencies, and destination beaches, which have made a seasonal week of unruly behavior a lucrative source of revenue.

How Contexts Drive Consumer Behavior

Sure, we can blame it on the coincidence that Ft. Lauderdale became the place for Spring Break. But for beaches in Miami, Panama, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic, this was far from a coincidence. Successfully mimicking an environment that screams beach, booze, and bad behavior is what neuromarketing is all about. Neuromarketing is the link between emotions and buying/partying behaviors.

Travel marketing is no different. Our context influences our actions. Our context acts as the default way to make decisions. In Hawaii, we don’t dare skip the Mai Tai’s. In New York City, we’d queue for the best slice of pizza. In Philadelphia, a cheesesteak sandwich sounds irresistible. We don’t leave Texas without trying barbecue and Boston without the seafood (unless you’re vegan, allergic to shellfish or worse, both).

Marketers are in the business of creating the perfect context to target our emotions, feelings, and desires to ultimately change our behavior. A timeless example is a city in the US dedicated to driving irrational, reckless behavior—Sin City. The 2003 tagline “What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas” is probably one of the most famous and contagious ever created. What started as an ad campaign is a mantra encouraging carefree, belligerent experience today. Marketers discovered there was one emotion bonding Las Vegas to its visitors: freedom; the freedom to be someone they couldn’t be.

The result of tapping into the virtue of freedom spiked Las Vegas’ number of visitors. In 2007, it hit an all-time high with almost 40 million visitors. (That’s like imagining the whole state of California on a drunken, gambling rampage!)

Source: Statista, 2020

Despite the dip in visitors during the Great Recession, people still have an emotional attachment to Sin City. The lesson? Context always prevails. With more than 42 million visitors in 2019, Las Vegas remains the default destination for those itching for a moral break. Never underestimate the silent power of the law of least mental effort, context, and default options.

Beyond the beaches, booze, and bad behavior, Spring Break’s about the virtue of freedom—the power to press the pause button on living a moral life.

As much as we love to let loose, let’s not forget that even in the Hangover, photos and videos of the night had resurrected and haunted the wolf-pack. But don’t worry, we won’t speak a word of it... 🙈🙊🙉

What’s Next?

References

Churchland, Patricia. Conscience: The Origins of Moral Intuition (pp. 168-169). W. W. Norton & Company. Kindle Edition.

Onlineschools.org: The Story Behind Spring Break

Patzelt, E.H., Kool, W., Millner, A.J. et al. The transdiagnostic structure of mental effort avoidance. Sci Rep 9, 1689 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-37802-1

Statista: Number of visitors to Las Vegas in the United States from 2000 to 2019

The New Yorker: The Strange Appeal of Perverse Actions, Paul Bloom

The Week: A brief history of 'What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas', Samantha Shankman

Dive into the fascinating intersection of psychology and marketing and how to use psychological biases in marketing strategy.