The Psychology Behind Celebrating Pride Month and Buying ‘Rainbow Products’

Photo by Mercedes Mehling, Unsplash

We’ve come a long way since Katy Perry’s breakthrough hit ‘I Kissed A Girl’ in 2008.

Every year, retail brands undergo an overnight mass makeover to celebrate Pride Month. Suddenly, the world is filled with rainbows—from the Converse shoes, (controversial) Marks and Spencer LGBT sandwich, to the packaging of KIND granola bars we buy. But is it only because there’s a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow?

Turns out, our Pride purchases give us a sense of moral superiority in our commitment to a social cause. Simply owning rainbow-colored shoelaces, for example, can signal we’re an ally. With the so-called ‘pink dollar,’ the purchasing power of the LGBTQ+ community, worth close to $1 trillion in the US, brands’ marketing strategy are undoubtedly effective. There is a (heavy!) pot of gold, after all.

To understand the tendency to voice our solidarity with social causes through purchases, let’s breakdown the psychology behind our beliefs, sense of belonging, and pride.

‘Coming Out,’ Cognitive Dissonance, and the Psychology of Beliefs

The LGBTQ+ population can often feel vulnerable because they constantly have to prove themselves, endure a tremendous amount of prejudice, and are underrepresented in media. The current culture assumes people are straight until otherwise blatantly stated on social media or in-person, which is why ‘coming out’ is an important aspect in validating one’s sexuality. The 2018 movie Love, Simon—a coming-of-age story set around closeted gay high school students—pokes fun at this concept in a scene where children come out to their parents as straight, highlighting the weight of how important ‘coming out’ is for the community.

The reality of ‘coming out’ creates an internal belief of having to be proud of one’s sexuality, but this internal belief can be exploited when you consider the role of cognitive dissonance. As we learned from the cognitive dissonance in veganism and our consumer behavior, we want to act in a way consistent with what we believe. For example, if we believe we’re a healthy person, then we’ll make conscious choices about what we eat, and so on. But if we make a choice that violates our internal beliefs (say, eating a delicious double-patty hamburger after a workout), there’s tension: enter cognitive dissonance. When there’s tension between inconsistent beliefs and actions, cognitive dissonance allows a person to either find some way to justify their actions (“This burger won’t hurt, since I worked out today anyway, right?”) or change their beliefs (“I’m not really a healthy person, I just like to workout a lot these days”).

The Psychology in Celebrating Pride

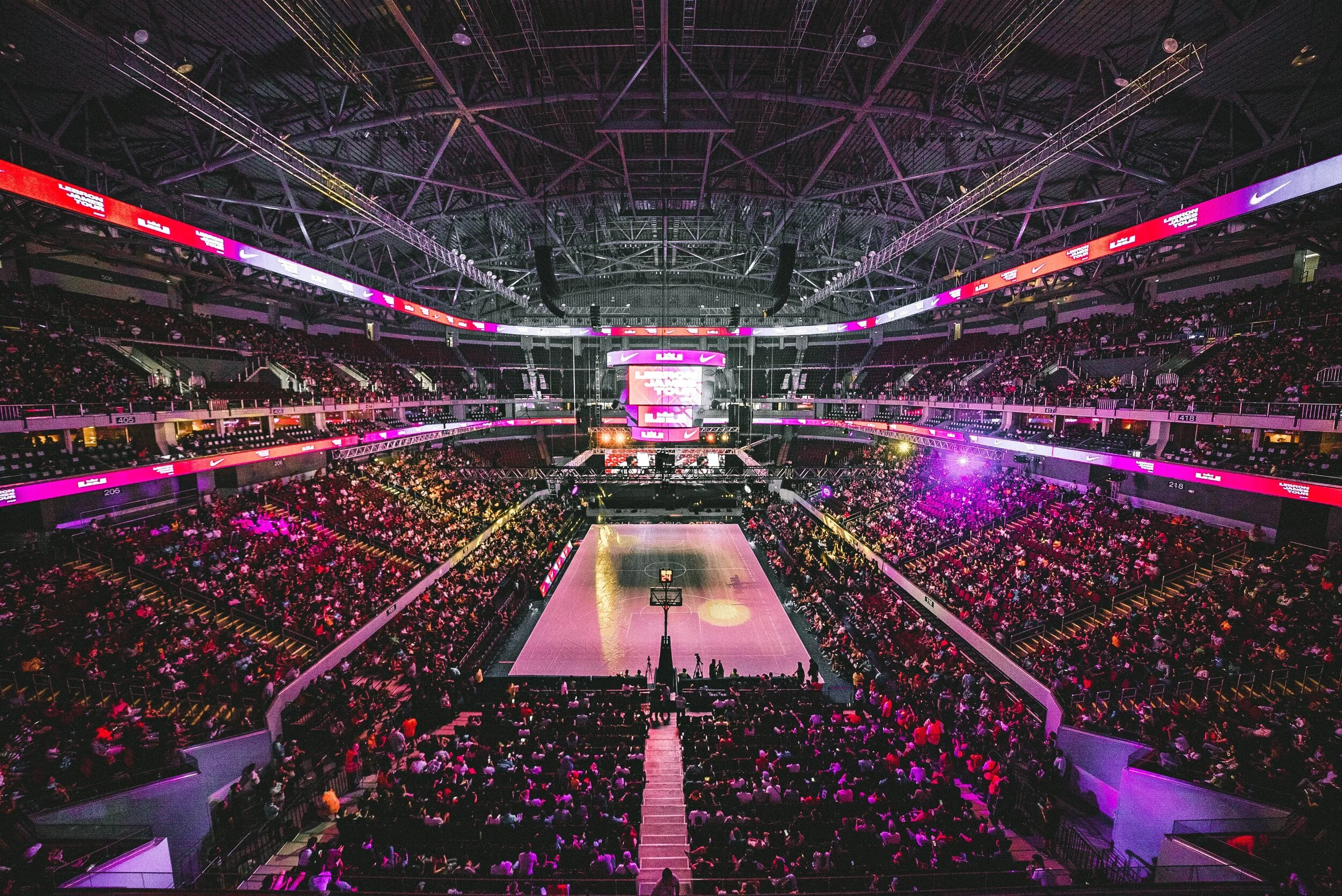

In relation to Pride Month, we return to the internal belief that members of the LGBTQ+ community should be proud of their sexual expression. Being proud of who you are is the essence of Pride Month—but also its pressure. To continue this internal belief of pride, we commit to actions enforcing it explicitly, like marching in any one of the Pride parades from San Francisco to New York, boycotting Coachella because its owner donates to anti-LGBT causes, or buying clothes from gender-inclusive brands like Wildfang. But what happens when something challenges a person’s ability to be proud? This happens with Pride retail when they add rainbows to their clothes just for the month of June.

Pride retail makes the assertion that a person who’s truly proud of their identity would be covered head to toe in rainbow to show their support. It becomes difficult for a person’s internal monologue of pride to be true without the ownership of products from this year’s rainbow line.

This belief that having rainbow clothing is synonymous with supporting a social issue extends outside the LGBTQ+ community too. Those who consider themselves “allies,” people committed to the advancement of LGBTQ+ rights without necessarily being part of the community themselves, are pressured into buying rainbow as well. The intertwined relationship of rainbow products and believing in social issues makes it easy for people to be pitted against their beliefs. To be consistent with our actions, an internal monologue goes something like this: You’re an ally, not a homophobe, so you must buy rainbow socks for the parade.

To explain the need to signal allegiance, let’s look at the influence of the love hormone.

Standing With Pride and a Cause

It’s extreme to have both owners of rainbow products and homophobes as part of the same spectrum, but it makes more sense when we consider the effects of oxytocin. Colloquially known as “the love hormone,” oxytocin helps us bond with each other within a group. But there’s a catch: the consequence of this in-group bonding also increases our dislike of outsiders, the out-group. This goes beyond Pride, and even extends to Harry Potter and K-Pop fans.

Many retail campaigns for Pride Month try to drive up oxytocin levels by creating campaigns with all inclusive messages aimed at Pride, which tend to be generalizable as well without the context of Pride. For example, SoulCycle displayed a rainbow sign with the phrase “All Souls Welcome,” while H&M used the hashtag “Love Happens Here.” These slogans attempt to bond people together to create a culture around those who support the mantra popularized by Hamilton musical creator Lin-Manuel Miranda, “Love is love.”

As a result of this increased in-group sentiment, oxytocin causes out-group resentment to increase. It becomes easier to think of the out-group in a very negative light, going as far as to accuse those without rainbow products as homophobic. This raises the risk of not buying rainbow products much, much higher. It’s not just internal consistency for ourselves that’s at stake, but a larger group encouraging us to make the purchase.

The Value of Rainbow Products

Is there really a problem with buying rainbow if we support the cause? Certainly, some organizations, like Adidas and ASOS, give 100% of their revenue from the pink dollars of Pride Month to the cause they are externally supporting—GLAAD, the Stonewall Community Foundation, and The Trevor Project.

There are many that simply use the rainbow power for branding to drive up their sales in a PR stunt without action. In order to see beyond them, it’s important to know the neuromarketing forces that might be manipulating our buying power. Despite what we may be told, buying rainbow doesn’t inherently mean we’re supporting a cause we believe in. In other words, if a company that has historically not been an active supporter of LGBTQ+ rights starts making rainbow products, then let’s be wary of where their pot of gold’s going.

Take it from Katy Perry, who has admitted ten years later that the lyrics to I Kissed a Girl are problematic today. It makes us wonder, how many other ways can brands spin the rainbow ten years later? Is this just the beginning?

The future of marketing is ever-changing. Happy Pride Month! 🏳️🌈

What’s Next?

References

CBSNews: "Rainbow retail" a biz opportunity in Pride Month and beyond, Megan Cerullo

Forbes: Retail & The Rainbow: 5 Ways To Navigate Gay Pride With Integrity, Positivity & Lasting Impact, Katie Baron

GuideVine: The Power of the Pink Dollar, John Schneider

Newsweek: These 50+ Brands are Celebrating Pride By Giving Back to the LGBT Community, Daniel Avery

NME: Katy Perry admits ‘I Kissed A Girl’ lyrics are problematic, Luke Morgan Britton

The Independent: Marks and Spencer Launches LGBT+ Sandwich To Raise Monday For Charity - But It Has Divided Opinion, Sarah Young

USAToday: How retailers have turned Pride month into a marketing, sales bonanza, Verena Dobnik

Vox: How LGBTQ Pride Month became a branded holiday, Alex Abad-Santos

Dive into the fascinating intersection of psychology and marketing and how to use psychological biases in marketing strategy.